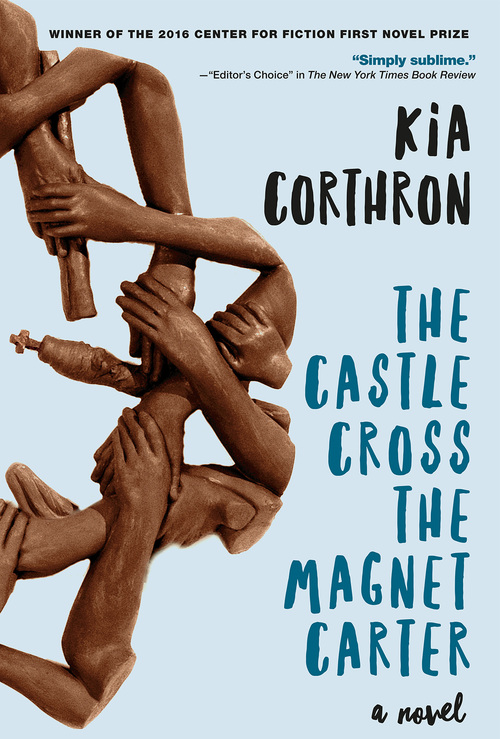

Winner of the Center for Fiction's 2016 First Novel Prize

The hotly anticipated first novel by lauded playwright and The Wire TV writer Kia Corthron, The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter sweeps American history from 1941 to the twenty-first century through the lives of four men—two white brothers from rural Alabama, and two black brothers from small-town Maryland—whose journey culminates in an explosive and devastating encounter between the two families.

On the eve of America's entry into World War II, in a tiny Alabama town, two brothers come of age in the shadow of the local chapter of the Klan, where Randall—a brilliant eighth-grader and the son of a sawmill worker—begins teaching sign language to his eighteen-year-old deaf and uneducated brother B.J. Simultaneously, in small-town Maryland, the sons of a Pullman Porter—gifted six-year-old Eliot and his artistic twelve-year-old brother Dwight—grow up navigating a world expanded both by a visit from civil and labor rights activist A. Philip Randolph and by the legacy of a lynched great-aunt.

The four mature into men, directly confronting the fierce resistance to the early civil rights movement, and are all ultimately uprooted. Corthron's ear for dialogue, honed from years of theater work, brings to life all the major concerns and movements of America's past century through the organic growth of her marginalized characters, and embraces a quiet beauty in their everyday existences.

Sharing a cultural and literary heritage with the work of Toni Morrison, Alex Haley, and Edward P. Jones, Kia Corthron's The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter is a monumental epic deftly bridging the political and the poetic, and wrought by one of America's most recently recognized treasures.

To celebrate today's publication of Moon and the Mars by Windham-Campbell Prize-winning writer Kia Corthron, we're proud to share an original piece by the author on creativity, grief, and finishing a novel as the world turned upside-down.

Creativity During Catastrophe

by Kia Corthron

I’m obsessive about waiting until a play or novel I’m writing is ready for production or publication before I let anyone read it — neither my agent nor my closest friends. Of course, I know the work isn’t really ready. For many writers, it’s part of their process to get reader responses (or, in the case of a play, to hear actors reading the work) early in development, while the author still has numerous questions to answer. For me, feedback is most useful when a legitimate first draft is complete. Reader questions then tend to be less generalized, more targeted.

A month into the pandemic shutdown, I’d reached this stage of “readiness” with Moon and the Mars. That timing, and the fact that my focus was on prose rather than a play, was fortunate. A couple of weeks ago, I was in email contact with an old composer friend who confided that the anguish of the past year had left him unable to generate new work, and his was far from the first such lament I’d heard. By contrast, because I happened to be near the end of a three-year journey with my book, the engine was moving too swiftly to be stopped: I was being productive which, for some of my hours anyway, was a distraction from all-encompassing despondency. Also, as craftspeople of the performing arts, my composer friend as well as most of my playwright colleagues have been dispirited by the live-audience precondition of our professions being reduced to, at best, many faces in isolated zoom squares. But for most of our social-distancing year, my own artistic energies were applied not to a play but to a novel, the writing intended not for an audience but for a readership which, by design, is a relationship built on work created in solitude to be read in solitude.

I completed the “ready” draft on April 15, 2020, and immediately sent it to my first readers, including the staff of Seven Stories Press, who’d published my debut The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter. Two days later, my sister Kim passed away. She was fifteen months older than I, succumbing to heart disease. At the time, COVID was raging in New York, making it impossible to get back to western Maryland where we both grew up. (She had been living just over the border in West Virginia.) My bereavement process was thus complicated by the fact that, other than phone calls, I had to mourn alone. I live in Harlem, and took early morning half-mile walks to the Hudson shore, listening to the quiet. I summoned up long-forgotten memories. I cried. I didn’t write. Had my sister died just a few days prior, before I’d put the final touches on Moon, I’m sure my novel would not yet be released as I would have stopped working for weeks. Or, had the manuscript already been submitted and contracts signed months before, deadline pressures may have materialized just as I was entering my shutdown to grieve. Instead, by the time that activity around the book began to kick in and editorial notes arrived, I had passed through the rawest phase of my sorrow, healed enough to undertake revisions.

The international horror dragged on, and I empathized with the countless losses worldwide as I diligently prepared Moon for publication. Even having endured my personal heartache, I marvel at the happenstance of narrow-window cosmic timing that impeded my fall into my own hole of despair — or at least prevented me from staying there.

Read More from Kia Corthron

How an Irish Syntactical Peculiarity Helped Me Find My Protagonist’s Voice

Kia Corthron on the Challenges of Dialect in Historical FictionRead more on Literary Hub

The Writer's Notebook: Kia Corthron on Urban Oases

Kia Corthron on exploring New York City's outdoor spaces — a practice that has brought her solace and changed her writing life.Read more on the Windham Campbell Prize site

Praise for Moon and the Mars

“Kia Corthron is a singular crucial creative artist with enormous vitality, re-imagining the real life of New York City rooted in new histories.”

—Sarah Schulman

“Kia Corthron has a knack for seeing what we cannot, for laying bare the truths we refuse to see. Moon and the Mars, her latest masterpiece, is an absorbing story of family and community, of Africans and Irish, of settler and native, of slavery and abolition, of a city and a nation wracked by Civil War and racist violence, of love won and lost. Unsettling the victim-perpetrator binary, she writes instead of people caught in the whirlwind of history, violence, politics, ideology, love, and desire; people navigating the actual world where race lines are drawn in shifting sands in blood and glue, elusive yet enduring, smelling of death and flowers. Corthron once again reminds us that nothing is black and white.”

—Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

“Theo is the lone narrator in Moon and the Mars, but her voice is so rich with the locutions and grammatical tics of her joint heritage that it sounds almost choral. The novel tracks her maturation until 1863 (followed by a coda set 15 years later), during which time her speech refines and her observations deepen. The plot is, effectively, history itself: Theo and her relatives struggle to maintain their dignity and decency, if not to simply survive, as they’re storm-tossed by the Dred Scott decision, the financial panic of 1857, the election of Abraham Lincoln and the start of the Civil War, among countless external tumults. The looming threat of fracture reaches a climax with the draft riots of 1863, in which an Irish mob enraged by federal draft laws targeted blacks, including children, in a spasm of arson and lynchings. Even here, Ms. Corthron is less attracted by the spectacle of violence [than] by understanding the tragedy’s causes and aftereffects... Ms. Corthron’s humility and curiosity match her outsize intellect and ambition. Her big, immersive novel almost never sermonizes; it is, however, eager to teach.”

—Sam Sacks, The Wall Street Journal

“Playwright and novelist Corthron combines a propulsive coming-of-age story with a fascinating history of the years before and after the Civil War... Corthron smoothly weaves in historical developments as divisions flare in the Five Points, such as the implications of the Dred Scott case, something Grammy Brook sums up concisely: “Whenever the rich make a crisis, you know what gonna fall to the poor is catastrophe.” Corthron’s ambition pays off with dividends.”

—Publishers Weekly

Praise for The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter

“There are whole chunks of writing here that are simply sublime, places in which one gets swept away by the way she subverts the rhythm of language to illuminate the familiar and allow it to be seen fresh... [Corthron] blindsides you. She sneaks up from behind. Sometimes, it is with moments of humor, but more often with moments of raw emotional power — moments whose pathos feels hard-earned and true... [The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter] succeeds admirably in a novel's first and most difficult task: It makes you give a damn. It also does well by a novel's second task: It sends you away pondering what it has to say.”

—Leonard Fitts Jr., The New York Times Book Review

“Kia Corthron’s first novel is a stunning achievement by any measure—a riveting saga of two twentieth-century American families trapped inside the quotidian contradictions and compulsions of race, disability, and sexuality. The untidiness of history is conveyed through experiences, dreams, and inevitable eruptions of violence, yet also unexpected patterns of escape and possible orbits of justice.”

—Angela Y. Davis, UC Santa Cruz

“When I first read it, I was stunned. It's a haunting and devastating tale, leavened with humor and hope ... I believe [The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter] is the most important piece of writing about twentieth-century America since James Baldwin's Another Country.”

—Naomi Wallace, Elle