Excerpt: “Field Notes from an Extinction” by Eoghan Walls

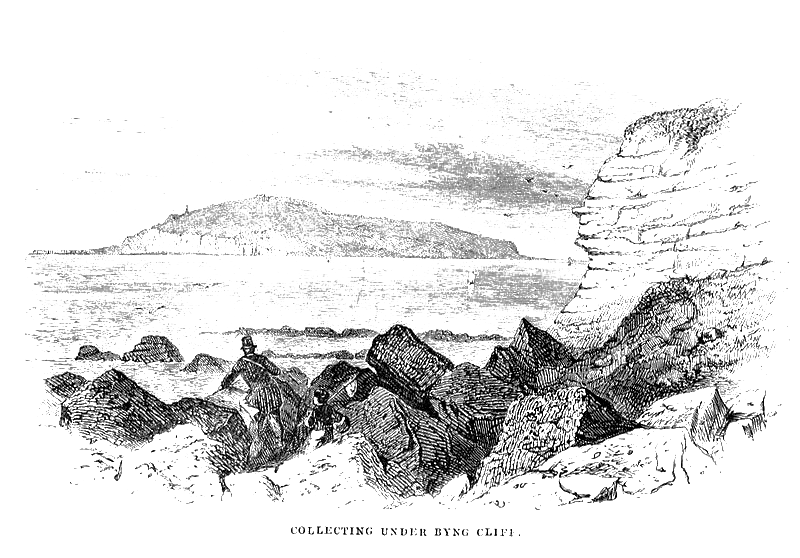

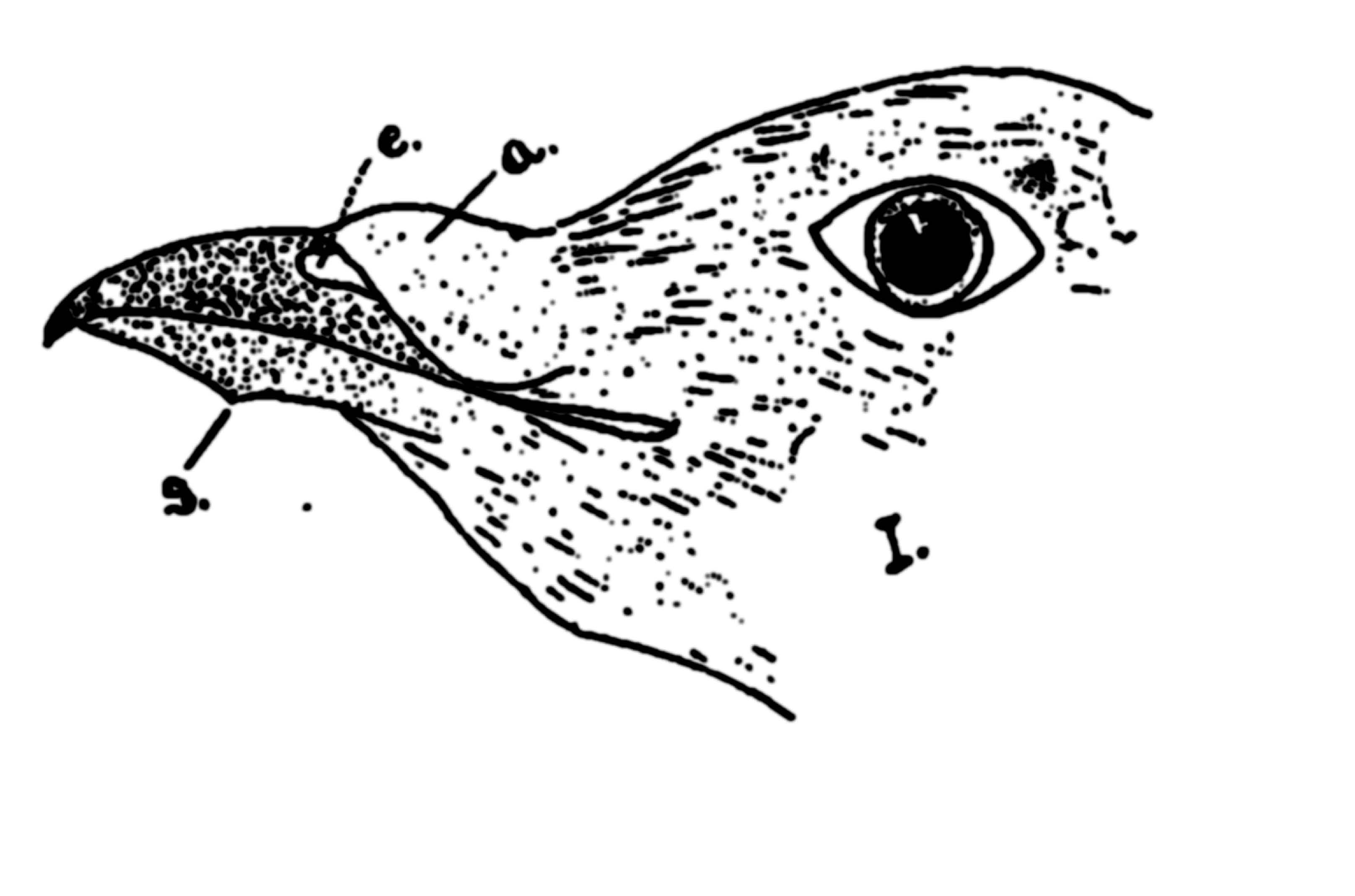

To celebrate the publication of Field Notes from an Extinction, the second novel by indie bookstore darling and acclaimed poet Eoghan Walls, we're proud to share an excerpt from the book, described by Graeme Macrae Burnet, in a new review in The New York Times, as "a unique and richly imagined novel." The extract, taken from the start of the book, begins the moment protatonist Ignatius Green realizes that a small child has stowed away on his boat and crashed his fieldwork mission to study the Auks on Tory Island, Ireland.

from

from

Field Notes on the Final Colony of Garefowl, vol. II

Monday, 31st May, 1847

The islandmen have smuggled a child onto Tor Mor Rock.

That I did not adequately register the basket in which the child was stowed is likely due to my state of perturbation at the obvious interference with my supplies. I was awaiting the delivery agreed already on October the 17th, 1846, with Hancock of Londonderry (formally of Staffordshire), in addition to supplemental grains to replace what was hitherto lost to rain, spillage & theft from the last delivery; to wit;

pease, one sack;

oatmeal, two sacks;

wheat flour, two sacks;

dried biscuit, one chest;

English cheese, one large wheel;

suet, a five pound slab;

butter, a five pound slab;

coal, five sacks;

whale oil, one bushel;

soured grog, one hogshead;

raisins, ten lbs;

dried apple, five lbs;

personal effects (ink, paper, etc), one chest;

replacement taxidermist’s tools, one chest;

brandy, two gallons;

lemon juice, one gallon;

fine tobacco (provenance immaterial), four lbs;

London gin, one gallon;

side of beef, one;

smoked Galician pig, one half-carcass.

Provisions enough for one man alone for one month entire on the rock with no need to journey inland. Missing this time was the beef; both sacks of wheat flour; one flask of brandy; the cheese. As further insult, much of the pig had been roughly cut away & but poorly wrapped thereafter, leaving only a ragged shoulder, the spine & bared ribs protruding from the torn bindings, left to rudely flap in the hail.

Even in the glum half-light of the late hail from Iceland, the theft was obvious, but the men were diffident, blank faced as poachers. Disputed with them at length on the shore. That thin pish Liam McGonigle is the only one of this batch admitting to passing competency in English.

MYSELF: The garefowl have laid, McGonigle. I cannot leave the island currently. It is an act of thievery that has been carried out here. Theft.

MCGONIGLE: I can only tell you again what I have told you already, sir, we bring you straightaways what we receive from Hancock. None of my men would dream of touching it, sure don’t we depend on the money you bring in.

His tone circumlocutory, his manner obsequious. His fellows scrawny, muttering their guttural tongue. He held the wet manifest to shield his face from the full force of the hail. I snatched it from him.

MYSELF: You are honestly trying to tell me you have not nabbed almost half of my provisions?

MCGONIGLE: I would be offended at the suggestion, sir.

MYSELF: Speak up, man.

MCGONIGLE: Offended, sir. I would be offended, sir. That is to say, no sir.

The ink wet on the page. The rest of the men, done unloading the goods, were already turning back to their vessel. Two thin boys—couldn’t be more than twelve—had already retired from manual labour, having fallen to coughing fits during disembarkation, & wailed loudly from the boat.

Skinny monkey youths, spluttering under a tarpaulin.

MYSELF: Do not turn from me, McGonigle. We are not done here. I must tally the rest of the shipment & keep an exact log of delivery.

MCGONIGLE: I must apologise but I am afraid further dalliance will not be possible tonight, sir. The tides as they are, we must get back before dark if we are to not come afoul of the Blind Rocks.

All his bluster & wheedling & still his uneven grin. He comes recommended by Sir Phillip. Worked with him on the tea ships for five years, supposedly one of the decent ones, & my reliance upon these islanders must extend another six to ten weeks yet. Sir Phillip will hang his head when he hears of his oversight in judgment! I shd have seized him, made him open each container before me. But his lank shipmen shook, coatless. It had taken three of them to carry a chest I could have easily managed on my own, & Connie’s lamentations of the starving Irish in her broadsheets must have addled my heart.

But not one of them would meet me in the eye, & one of them, I swear, was laughing into his sleeve.

MYSELF: What are they saying, Liam?

MCGONIGLE: What, sir?

MYSELF: That one there. What did he say?

MCGONIGLE: It is untranslatable, sir.

Half of them wading already into the choppy black sea, trousers still dark from disembarkation. McGonigle would only heed me when I held him.

MYSELF: Do not turn from me!

MCGONIGLE: (gesturing to youths on the boat) My nephews, sir. I have to get them out of the squall.

MYSELF: You think I am at your mercy, McGonigle. But it is you & your family who are dependent upon my good graces. Sir Phillip will hear of this.

MCGONIGLE: (utterly unabashed) I will inform him myself of the missing supplies, sir. Your unhappiness is my unhappiness. But I can only tell you again, I have delivered exactly what we received this morning.

He squinted into the wind. One of the youths wailed to him from the boat. But before he stepped into the tide, he touched his nose & leaned towards me.

MCGONIGLE: I advise you strongly to unbox the goods tonight.

MYSELF: What?

MCGONIGLE: Tonight, sir. Unpack the goods tonight. Before the gulls quite eat your pig away, sir.

I looked up the beach. The herring gulls were indeed tugging wildly where the meat hung loose.

MYSELF: In a month, I expect a full half-pig, Liam.

MCGONIGLE: I will make sure to pass on your words, sir. But unpack it tonight.

The islanders launched as I headed back up the rock, chasing gulls off the pork with the manifest. I believed I had the size of the matter, by which I mean the theft, but wanted to ensure my tools were intact, & then secure both the oats & the biscuits, as I have missed both sorely, & took my time getting around to the tarpaulins, my sight & hearing much reduced by hail. Odour I detected none; my nose is near bleached by the slant wind & constant exposure to fishy guano. Thus I failed to register the child or even the basket that bore it until the men had nigh passed the Organ Pipes.

But I could smell it indeed when I bent to examine the barrels. Even in the wind, sour as meat, the stench of human waste.

It made no discernible sound as I tugged off the tarpaulin. A wicker basket big enough for a live pig. At first, I thought I had found the side of beef gone rancid; but the weight of the basket shifted as it tilted; then I tugged the lid & knew not what I saw.

Two eyes met mine in the dark.

A face. A child.

A child blinking in the half-light.

Two wet eyes. A nest of hair.

MYSELF: Wait! Wait, you madmen! Wait.

MYSELF: Wait! It will die, you madmen! The child will die!

I ran towards the Organ Pipes, skidding, landing heavily off the lower ledge. Rose uninjured, shouting. The islander skiff was maybe three hundred yards out. Faces of the islandmen distant.

They made as if not to register me.

They saw me though. I know they did.

I was not done. Ran back to the basket, tugged it loose, heaved it to my chest & bore it on the rocks, tho it was heavy, & dropped it into my little rowboat, whereupon it toppled on its side & the lid slipped & the child rolled onto the shale screaming. Lifted it, tho it arched its back, into the darkening sky.

MYSELF: Take it back. I cannot take it. Take it back!

Waded in to my waist. Soaked my good green trousers, my boots wet thru, undergarments too. Shouted, at length, holding the child over the sea, a writhing thing, squealing, its apparel stinking.

The men had their backs to me now, & the boat disappeared behind the waves.

MYSELF: Take it back. It will die here. It will die!

My face & ears stung in the hail & the child’s most likely too, tho it gave up kicking & screaming to simply hang, until I stumbled back to the shore & dropped it to the shale.

The islanders were too far out.

In the waves & stormy dusk, with their sails up, I would not catch them in my little rowboat.

They have lumbered me with a thing that mewls on pebbles.

MYSELF: Get back in the basket. Get up. Into your basket.

MYSELF: Get in the basket! You are filthy.

No English in the child. It squealed on approach & on contact. All filth & frail wiriness. For humanity’s sake, I might have carried it in my arms, but the bloody thing seized like a board at my touch & writhed, & it proved altogether easier to just drop it back into its basket & carry it like goods.

Its basket now stands at my stove.

Must attend to deliveries. The gulls have picked thru my hasty rewrapping & are worrying my meat once again.

~

My supplies—or what I have of them—are secured.

The child has not moved.

Initially, it seemed entirely mute.

MYSELF: I must see to the deliveries. I must bind them before the gulls spoil them. (rattling the basket) If I do not go, I will lose the meat. You understand?

The child sobbed, mostly in silence, but yelped at the sight of my hands. So I unpacked my goods, first in hail, then in twilight by lamplight, as the sky cleared to a cosmic chill & Andromeda popped thru the clouds. First carried & hung the meat inside & the various perishables, then the pease & oatmeal, then two chests of tools behind my partition, then bound both dry goods & imperishables in sailcloth in the cabin’s lee. Could tell McGonigle had got back to Inishtrahull as his lighthouse began its repetitive scything across the shale & sea beyond Tor Mor. By the time all was secured, the wind had died & a fat full moon chipped the edge of a clear horizon.

The brandy—the single flask I have—is unwatered.

The biscuit coverings are unbroken.

Neither the butter nor the suet have spoiled.

All this time, the child lay silent in its box, by the stove, the fire on full blast, under the bubbling still. It—she, by the pinafore, she—must have been near roasted. The still gives a raging heat at full blast—I have coal enough for weeks, as it appears the Irish cannot eat coal—& the only shelter the child had was its rough & soiled wicker.

I heaved the basket to the door, naturally.

It—she, she—was silent the whole time & but for the heaviness & rapidity of breathing, I might have thought her dead.

MYSELF: You can come out here if you want to.

MYSELF: Come out. I will not hurt you. You can come out.

MYSELF: I am a good man. I am not unkind.

MYSELF: Are you not able to climb out? I will set the basket on its side.

Small yelps as I tilted the box, then nothing. At her continued silence, I peered into the depths, where she was coiled like a beast among her particulars, namely:

Clothing she wore;

a shitten, once white dress;

one blanket (utterly soiled);

one pair of wooden clogs;

one cracked chamber pot, once affixed to the base, now unmoored;

one rubber-bunged pewter flask.

The latter despite the age of the girl. Eight? Five? Twelve? I can age a puffin reliably to the season but with a human child could easily be off by four years, give or take. Malnourished, by the look of her, which makes the judgment harder. Just over my waist at full extension I would estimate, closer to four foot than three, skinny & dull of wit, lacking in vigour, filth-cauled & whimperish.

MYSELF: You can come out of the basket. I will not hurt you.

CHILD: Wishke.

This it croaked. Its first word: Wishke. Gaelic. Obviously there is opportunity for drollery—even Irish children clamour for whiskey etc—but from conversations with Frank, I know the word to mean water.

MYSELF: Water. You mean water, yes? Do you want a drink?

The child flinched as my hand neared. I took its—she, her—her bunged flask, a filthy receptacle possibly for use at sea or in prisons, & there was no strength in her hold on it. Filled it from the cooling tub by the still, returned it to the lip of her basket, & her little talons snatched it back.

Watched her drink. The matting of her hair almost total. Waste visible on the remains of what was clearly once a pretty outfit. What were once ribbons are now twisted & frayed.

MYSELF: Wishke. Wishke means water.

MYSELF: Do you want food?

MYSELF: Where is your mother, child?

Might as well have talked to a stone.

Dinner simple but wholesome. Boiled oats & sliced bacon shoulder. Have missed the bacon much. Must ration it carefully now. Oats too. Dregs of old lemon juice softened the meat & a tumbler of grog. Made a little extra. The child can eat with me one night. As I cooked, I tried to engage her. Box on its side. All I could make out from the shadows was greasy hair.

MYSELF: Grog? Do you want some grog?

MYSELF: Are you hungry? Do you want porridge?

CHILD: Wishke.

Refilled her bottle a second time, had it snatched again.

MYSELF: We will have dinner. We will eat. Food? I can feed you tonight.

MYSELF: Can you speak, child?

MYSELF: (chopping bacon finely) You can eat with me tonight. You are very welcome. Then, in the morning, I will take you back to the island. Do you understand? Back to your mother.

Not a flicker of comprehension, even at the word mother. But surely their Gaelic word must share some root with mater, mere, mutter? I have no idea.

She was entirely fixated on drinking.

Then I noted a puddle seeping from the basket over my boards.

MYSELF: No! No piss in here!

The child screamed as I dropped the knife & leapt to carry her & the dripping basket into the dark to the shale by the outhouse.

MYSELF: You do not piss in the cabin. Hear me? You do not piss in the cabin. Piss here. Piss out here. No piss in the cabin! Piss out here!

The child, distraught, keening. I thought of house-training hunting dogs, & rattled the basket, & shouted some more.

MYSELF: Do not piss in here. Children piss outside. We all piss outside. Everyone pisses outside! Not in the house.

Scrubbed the boards, & once her noise died down, carried the basket inside, dumped it by the stove. Set up table, added brandy to the oats, a sprinkle of sliced apple. Two bowls, two stools, & turned the basket so she would have to face me.

MYSELF: Come out of the basket now. It is time to eat.

MYSELF: Eat. Good food. The porridge is good.

MYSELF: Child! I will not bite you.

MYSELF: Child. Listen to me. I do not know if you can understand me, but it is only fair that I explain to you the situation. I will feed you & put you up for tonight & we will return you to your island in the morning. Whatever nonsense McGonigle is playing will be short-lived & I am sorry you are suffering but I am as much a victim in all of this as you. I do not know your full situation but I am here on vital scientific business & while I have all the sympathy in the world for the destitute, I cannot allow you or anyone else to interfere with my studies. I will take you home in the morning. So please, I ask you. Take my food. This is a strong & nourishing porridge. Eat it. It is good.

Not a word in her head. Perhaps she is dumb, or an idiot? When I proffered her a spoon, she sucked on her bottle instead.

MYSELF: Damn you so.

Am tired now from manual labour. Gin is a salve. This whole episode a pointless irritation. I must write to Sir Phillip immediately, outlining the loss of provisions as well as the islanders' tomfoolery, & seal it definitively so as to make sure McGonigle cannot doctor the contents.

~

The child spoke as I was writing, but merely to ask for wishke, wishke! Like a wretch in an alley, she had crawled to the edge of her hutch, blinking in lamplight. For the first time I saw the face under her dank fringe, tear-streaks in mud, a moustache of puckered scabs.

Then, as I handed her the bottle, noted once again a thick stream of piss along the boards.

MYSELF: No! I told you! I told you!

Snatched her up, this time my hands in her hot armpits, regretting the closeness instantly as I bore her high & streaming out the door. She had pissed on my overalls, & where I had touched her, there was grime on my hands.

Bellowed at her, somewhat immodestly.

Then had to touch her again as I carried her wailing & dripping back to her box.

I have scoured the piss now, twice.

I can still smell it. The piss, & the whole child, despite the application of lime.

The situation is ridiculous. I had heard of such things in Barrackpore. Mothers prepared to risk the life of their offspring on the chance generosity of civilised men. More normally a man is protected by the trappings of civil society, his boy or domestic help interceding before the destitute can encroach. But never have I heard of a scientific expedition so disrupted.

It will not be without repercussions. McGonigle’s men have not only taken my provisions but now threatened my peace of mind. If Sir Phillip cannot guarantee adequate sustenance & appropriate intellectual solitude, the entire venture is imperilled; if further funds are required for the security of the next delivery, he needs but ask the Royal Society.

Have written him as much.